.png?width=1280&height=720&name=Training%20a%20custom%20model%20v2%20(1).png)

3 Historical documents that create more mysteries than they solve

Old letters and manuscripts are important sources for historians. They offer a direct window into the past, showing us everything from the private thoughts of world leaders to the daily life of an ordinary person. Often, these texts hold the very answers we need to understand our history, helping researchers piece together events and solve long-standing puzzles.

But what happens when a document doesn't solve a mystery, but creates one? Sometimes, a historical source leaves us with more questions than answers. An anonymous author, an unbreakable code, or a chilling message can turn a simple piece of paper into an enduring puzzle that baffles experts for generations. In this post, we're going to explore three such mysterious documents from history and the theories about who wrote them, what they mean, and the secrets they might still be hiding.

Content Disclaimer: This blog post discusses historical events and materials that include descriptions of violence and death. Reader discretion is advised.

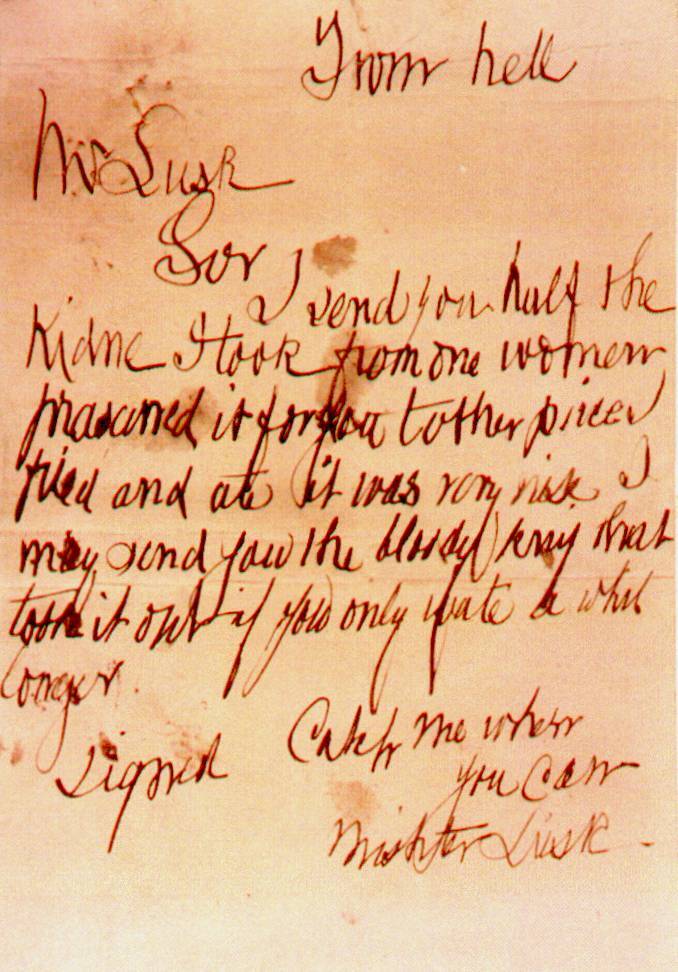

The "From Hell" letter is one of many the police received proclaiming to be from Jack the Ripper. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The ‘From Hell’ letter and the shadow of Jack the Ripper

In the autumn of 1888, the Whitechapel district of London was in the grip of a terror campaign conducted by a serial killer known only as Jack the Ripper. Amid the public panic and police investigation, hundreds of letters claiming to be from the killer were sent to the press and authorities. Most were quickly dismissed as hoaxes, but one, received on 16 October 1888 by George Lusk, chairman of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, stood out for its horrifying contents. The package contained a small cardboard box in which lay half a human kidney, preserved in ethanol, alongside a short, poorly written letter.

The note, which began with the infamous salutation ‘From hell’, was a taunt to Mr Lusk. The author claimed to have fried and eaten the missing half of the kidney, stating it was ‘very nise’. The kidney was thought to belong to Catherine Eddowes, one of the Ripper’s victims, who had been murdered on 30 September and had her left kidney removed. Unlike the more famous ‘Dear Boss’ letter, which is widely considered a journalistic fabrication, the ‘From Hell’ letter is treated with more seriousness by researchers due to the physical evidence that accompanied it. The central mystery is its authenticity: was it a genuine message from the murderer, a gruesome trophy sent to provoke fear and mock the investigation, or a macabre prank by someone with anatomical knowledge, such as a medical student? The original letter and the kidney have since been lost, leaving only photographs and witness accounts, ensuring that this chilling piece of correspondence remains as enigmatic as the identity of the killer himself.

The Voynich manuscript contained not just text in an unknown language, but images of unknown plants. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Voynich manuscript: A book that cannot be read

The Voynich manuscript is not a single letter, but an entire 240-page codex that has defied every attempt at interpretation for over a century. Housed in Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, this vellum-bound book was carbon-dated to the early 15th century (1404–1438), yet its author, language, and purpose remain completely unknown. The manuscript is filled with a unique, elegant script that corresponds to no known language, and is lavishly illustrated with bizarre and fantastical drawings. These illustrations divide the book into distinct sections: botanical, with detailed drawings of plants that are unidentifiable; astronomical, featuring celestial charts and zodiac signs; biological, with images of naked women bathing in intricate plumbing systems filled with green fluid; and pharmaceutical, showing what appear to be medicinal herbs alongside text.

The profound mystery of the Voynich manuscript is whether its text contains meaningful information or is simply an elaborate, meaningless hoax. The text exhibits clear linguistic structures; for example, it follows Zipf’s law, a statistical distribution of word frequency found in natural languages, and its entropy is similar to that of Latin or English. This suggests it is not random gibberish. Yet, the world’s most accomplished cryptographers, including the codebreakers who worked during the First and Second World Wars, have failed to decipher it. Theories about its nature are wide-ranging: some propose it is a lost natural language, a cipher hiding another text, a work of glossolalia (speaking in tongues), or a sophisticated forgery created to defraud a wealthy patron. Until a key is found to unlock its script, the Voynich manuscript remains a silent, beautiful enigma, a book written in a language that may only have ever been understood by its creator.

.jpg?width=5530&height=8399&name=default%20(2).jpg)

Primary sources, such as this letter from Cotton Mather, help historians understand the cultural mood at the time of the Salem Witch Trials. Boston College collection of Cotton Mather letters, MS.1990.023, John J. Burns Library, Boston College.

The Salem Witch Trial and the mystery of mass hysteria

In 1692, the Puritan community of Salem Village, Massachusetts, was consumed by a wave of witchcraft accusations that led to the execution of 19 people and the deaths of several others in prison and during torture. The enduring mystery of the Salem witch trials is not about a hidden code, but a profound historical and psychological question: how did a community of seemingly rational individuals descend into a deadly mass hysteria? One might look to the letters of influential figures like the minister Cotton Mather for answers, but his writings often complicate the picture rather than clarifying it.

A letter Mather sent to chief magistrate William Stoughton on 31 March 1692 perfectly illustrates this complexity. Written just two months after the first accusations, the letter shows a man deeply embedded in the era's cultural fear of the supernatural. He warns of “wicked spirits in high places” and his belief that the “devil do more easily proselytise poor mortals into witchcrafts than is commonly conceived.” This mindset clearly provided intellectual fuel for the trials. Yet, in the very same letter, Mather displays a surprising degree of scepticism. He cautions Stoughton against relying on confessions—a cornerstone of the trials—warning they could easily be the product of a “delirious brain or discontented heart.” This contradiction at the heart of Mather's reasoning makes the entire event more baffling, showing how a society's intellectual leaders could both see the dangers of the process and simultaneously help it continue.

Solving the mysteries of history with Transkribus

From the blood-stained streets of Whitechapel to the paranoid village of Salem, these enduring mysteries show that a simple piece of paper can be as baffling as any archaeological ruin. The ‘From Hell’ letter, the Voynich manuscript, and the conflicted writings from the Salem Witch Trials all serve as powerful reminders that history doesn’t always give up its secrets easily. They leave us with tantalising puzzles about their authors, their meaning, and the worlds they came from.

While the primary job of solving these historical riddles falls to historians, archivists, and researchers, modern technology, such as the Transkribus platform, offers powerful new ways to approach the evidence. Transkribus provides the tools not just for transcription but also for the systematic analysis of historical texts. Faced with a mountain of complex and confounding sources, researchers can use Transkribus to organise, tag, and search documents with incredible efficiency, helping them piece together the clues needed to understand who wrote them, when, why, and how.

In short, while Transkribus may not be able to identify Jack the Ripper or translate an unreadable book, it empowers the experts who can. By bridging the gap between historical documents and digital analysis, it helps turn daunting mysteries into solvable questions, one page at a time.

-1.png?width=1280&height=720&name=Types%20of%20historical%20Sources%20(1)-1.png)

.jpg?width=1126&height=1536&name=Voynich_Manuscript_(33).jpg)

.png?width=1280&height=720&name=Featured%20Image%20(11).png)