.png?width=1280&height=720&name=Featured%20Image%20(12).png)

Mapping the concerts of Beethoven and Haydn: the “Concert Life in Vienna” project

Some Transkribus projects finish with a complete digitised collection in Transkribus. Some take that digitised source and use it to contribute to a wider project.

“Concert Life in Vienna” is a project of the latter variety. A research team at the University of Vienna is currently creating a database of concerts and cultural events in the city from 1780 until 1830, the era of Beethoven, Haydn, and Schubert. The database will allow scholars and the general public to search for information about concerts in the city, including the music, the venue, and the people present, and even allow users to listen to the music as if they were in the room.

We spoke to Mary Kirchdorfer, a PhD researcher on the project, to find out more about how Transkribus is contributing to this epic project.

Vienna at the centre of the classical musical world

At the turn of the 19th century, Vienna was one of Europe’s key cultural hotspots. Home to Haydn, Schubert, and, most famously, Beethoven, it became a hub for musicians and composers as they transitioned the art form from the “classical” to the “romantic” period. But because the city didn’t have an official music venue until 1831, concerts and musical events were organised differently, taking place in palaces, salons, or even coffee houses.

It is these concerts that Mary and the “Concert Life in Vienna” project wants to map out. The team’s database will contain information from a very wide range of sources, helping to create a comprehensive bank of all the musically relevant people, works, venues, and performances in Vienna during the time period.

“Our database aims to consolidate and verify the accuracy of what is already known about concert life from secondary sources, and filling in what is still unknown about these concerts by assessing various untapped primary sources.”

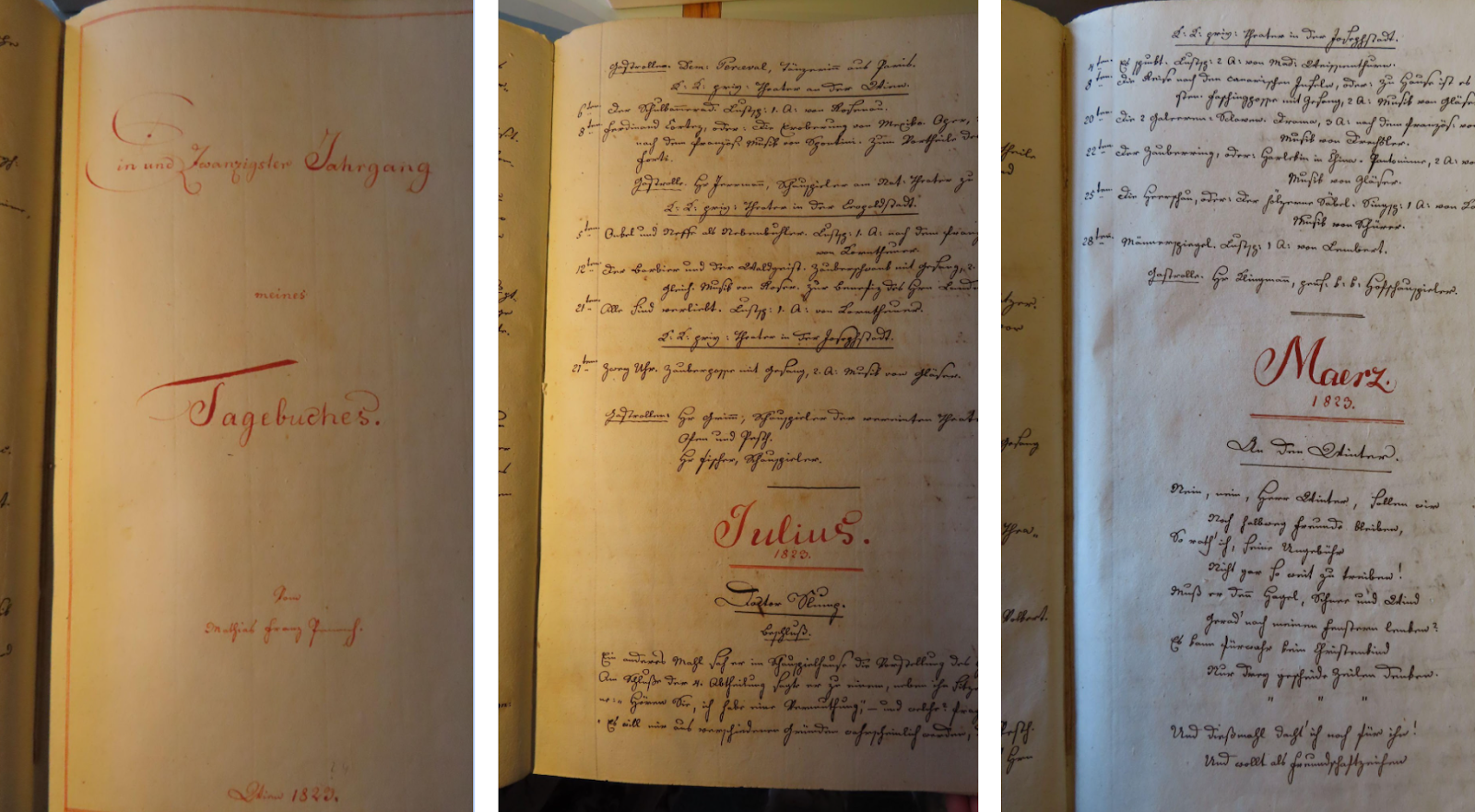

Unlocking the diary of Matthias Franz Perth

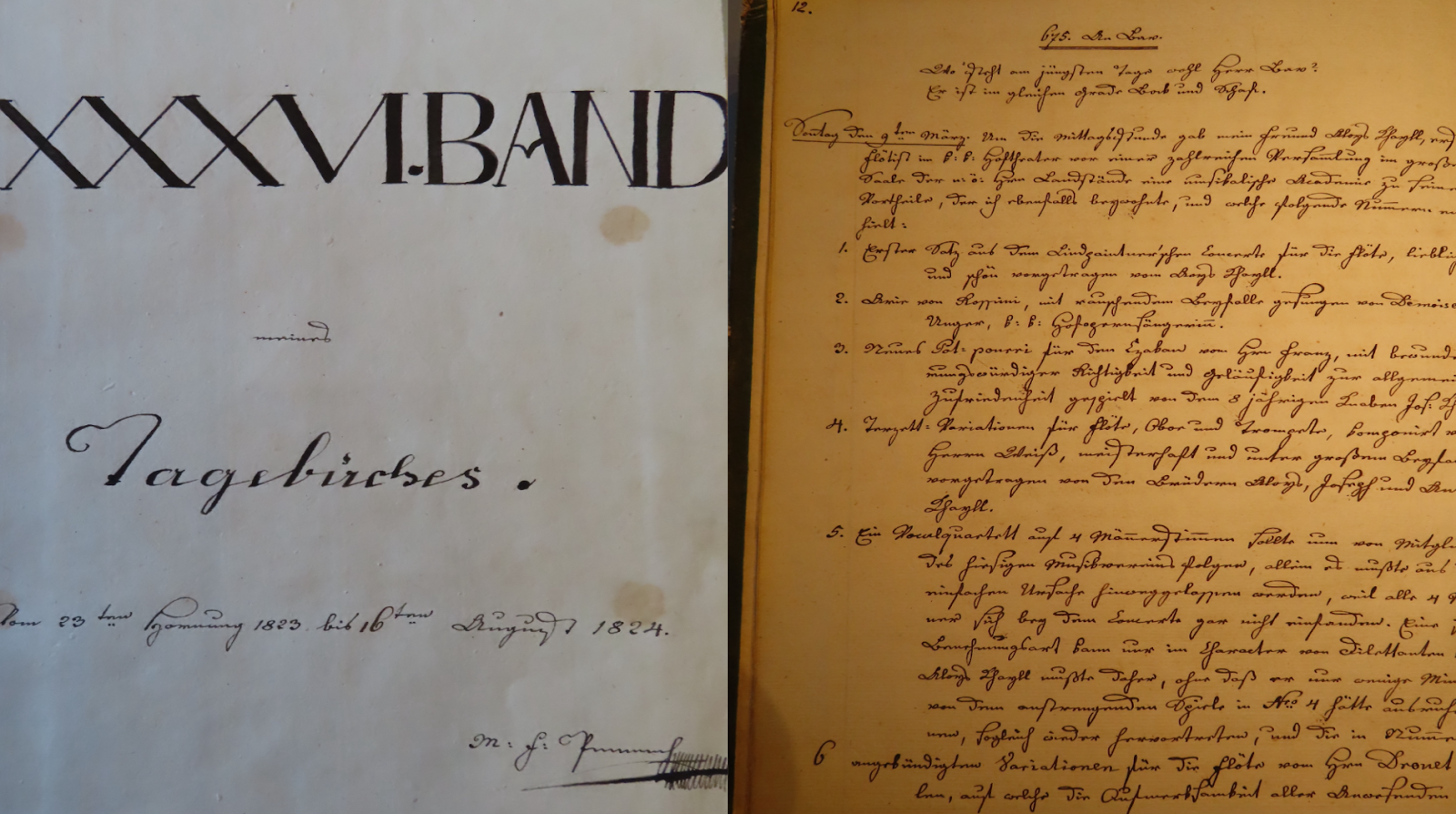

One of those primary sources is the diary of Matthias Franz Perth. Perth was neither a composer nor a musician but rather a city administrator with a passion for diary writing. “Perth is known in many scholarly disciplines, mainly because he kept meticulous diaries for 53 years, sometimes writing over 500 pages for one year alone,” Mary explained.

While many of his diary entries cover the mundane parts of life — for example, which Bierhaus he went to, the cost of milk, and tables detailing inflation — Perth also wrote detailed descriptions of cultural events such as classical concerts, live music in coffee houses, parties, balls, and theater performances. These descriptions are a valuable source of information for the “Concert Life in Vienna” database.

“For our project, I am concerned with the full concert programs he copied out into his diaries, especially salons, or those happening in a more intimate context,” Mary said. “Many of his observations are not included in the newspaper coverage, or he will describe an event that was not in the newspaper at all. We hope to use his eyewitness account to clarify who performed which musical works, and in which venue.”

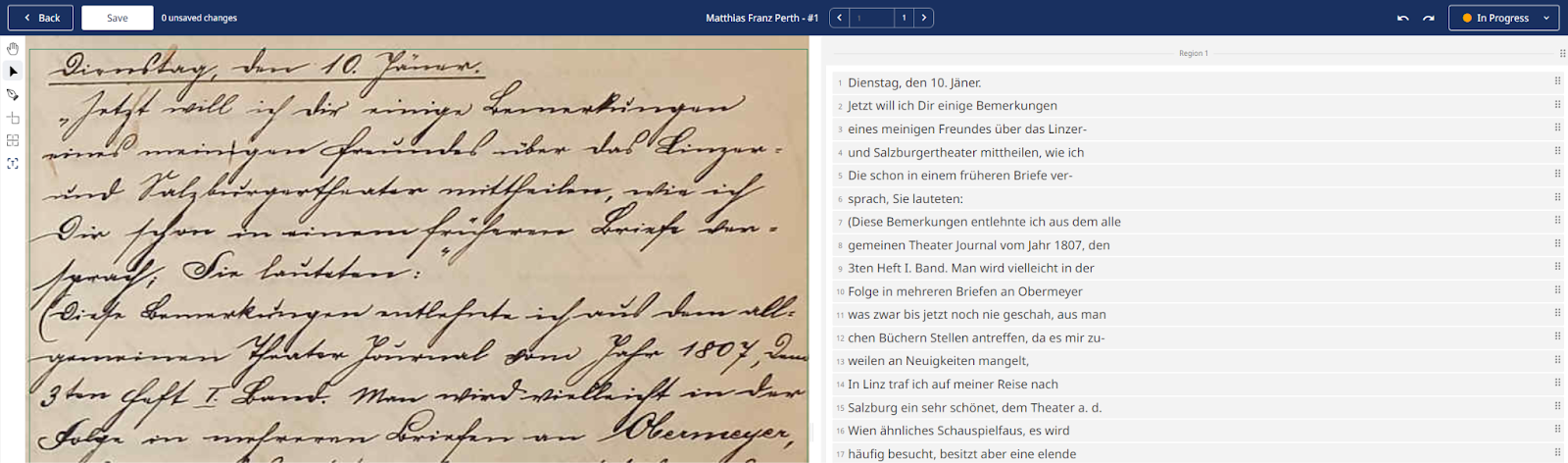

First steps with Transkribus

Before the age of AI, Mary would have had to painstakingly read through each of Perth’s diaries and manually note down the details of the cultural events he describes. “The sheer amount of handwritten material would take ages to comb through. In just the 1823-1824 concert season, Perth [wrote] almost 600 pages.”

Instead, the team wanted to speed up the process with technology and decided to transcribe Perth’s diaries with Transkribus. “Using Transkribus will allow me to find information about Viennese musical life at a much […] more productive pace,” Mary explained. “ I have just finished 50 pages of editing, which means we have enough corrected material to train our own model for Perth’s diaries. I assume we will be able to grasp what else is in this diary [much more quickly], and then add it to our database.”

Using Transkribus has another added bonus: “My own ability in reading “Kurrentschrift” has also improved dramatically!”

The lesser-known side of Perth

While Mary’s main focus is the concerts and cultural events described in Perth’s diaries, the contextual information surrounding these is invaluable too. “I have learned so much about daily life in [this] time period. This will help me write about the context of Viennese concert life in my dissertation.”

In addition, Mary has discovered some interesting nuggets of information about Perth’s private life. “Perth was a bit of a history buff himself,” she told us. “For every dated entry, he also includes a “history calendar”, where he explains what happened “on this day in history.” This includes music history, war history, and even medical developments like the first vaccine for cowpox.”

“I have also discovered he was very close friends with Aloys Khayll (1791-1866), the flute virtuoso who played with Beethoven and for the Burgtheater. They often went to the Gasthaus “zu den 7 Sternen” to play cards together.”

Recreating the concerts digitally

The “Concert Life in Vienna” database is a work in progress. Currently, the 1823-1824 concert season is the only one that has been completed in full, with details for over 1000 relevant people and over 200 concerts.

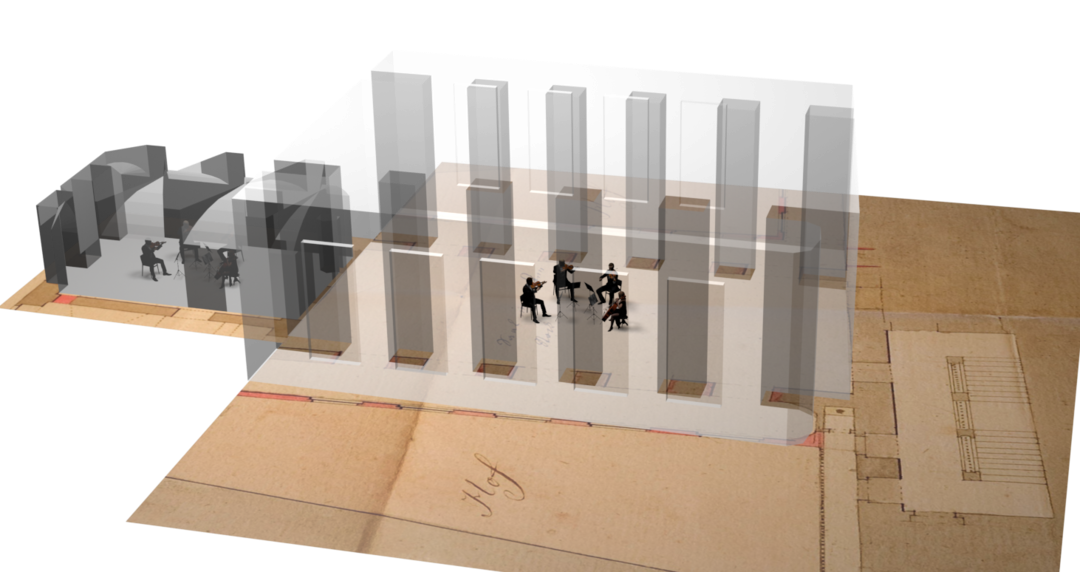

However, the “Concert Life in Vienna” project doesn’t just aim to let users read about the events that took place but also visualise them through the creation of an interactive map of all the different events. Users will even be able to experience the concerts for themselves, thanks to a collaboration with the Technical University of Berlin.

“[Our colleagues in Berlin] are working with us to measure the acoustics of some of these concert spaces (those that have not been remodelled) to recreate the music in these rooms. The end user can also choose where in the room they are listening (in the doorway, the front row, the back row, etc.) to hear the acoustic differences. This will […] allow the end user to hear some of these concerts in their original room.”

Making historical documents accessible

Of course, there is still plenty of work to do on the “Concert Life in Vienna” database. Mary and her colleagues are currently transcribing the rest of Perth’s diary using Transkribus, not to mention harvesting data from many other primary sources written in the era. But while the project is still in its infancy, the initial public reaction has been strong. The database was presented publicly for the first time at an International Conference commemorating the 200th anniversary of the premiere of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony, receiving much acclaim.

For Mary, though, the project is not just about publicising the already well-known musical works, but by giving people the tools to uncover previously unknown events and works. “I hope that our database allows for more accessibility to historical documents concerning Viennese concert life, just as Transkribus is making our past more legible. It is an incredible tool for any project handling historical documents.”

Thank you, Mary, for telling us about your project.

Update: A dedicated website is now live, presents insights from the ongoing WEAVE research project: Concert Life in Vienna 1823-25

Thumbnail: Mary Kirchdorfer

.png?width=1280&height=720&name=Training%20a%20custom%20model%20v2%20(1).png)