.png?width=1280&height=720&name=Featured%20Image%20(12).png)

What is Carolingian Minuscule?

When you think of Carolingian (or Caroline) minuscule, Charlemagne and his vast Carolingian empire likely come to mind. While the origins of the script trace back to the time before Charlemagne, it was during his reign that the script became popular, helping to promote literacy throughout the Holy Roman Empire and making it easier to copy and distribute religious and secular texts.

Today, this medieval script serves as a window to the past, offering insights into the culture, language, and artistic tendencies of the Carolingian era. For researchers of medieval history and Latin paleography, understanding Carolingian minuscule is key to unlocking many of the documents from the period. In recent years, AI platforms such as Transkribus have played an increasingly large role in this process.

In this article, we’ll delve into the development and continuous significance of this unique form of the Latin alphabet, from its initial creation in the late 8th century to its lasting importance in the modern world. We will also look at how Transkribus’ handwritten text recognition technology assists scholars in deciphering Carolingian minuscule and provides a valuable tool for unlocking the past and deepening our understanding of the Middle Ages.

Carolingian minuscule or Caroline miniscule ?

Before we start, you might have wondered why there is more than one spelling variant of Carolingian minuscule. So, let’s first clear up any terminological doubts.

As you might know from your Latin lessons, ‘minuscule’ is the Latin term for ‘very small’, and is used as a general term for lowercase letters and types of writing consisting of such letters. It can also denote historical scripts written in a quattrolinear scheme, featuring letters with extensions (ascenders and/or descenders).

‘Miniscule’, however, is a misspelling that has gained popularity due to the misconception that ‘minuscule’ is related to ‘miniature’ or ‘mini’, which also means very or rather small. ‘Carolingian miniscule’ is increasingly used online.

One last thing: the adjective ‘Caroline’ can be used interchangeably with ‘Carolingian’, as demonstrated in this blog post.

The origins of Carolingian minuscule

There used to be a long-standing belief among researchers that Carolingian minuscule was created at Charlemagne’s court in Aachen as part of the Carolingian Renaissance in the late 8th and 9th centuries. However, the first manuscript containing an early form of this script was actually written at Corbie Abbey in France before Charlemagne’s reign had even begun. Recent research suggests that a prototype of Carolingian minuscule originated in the scriptorium of this abbey as a result of experimenting with different writing forms.

It was under Charlemagne that the script then became popularised. Charlemagne, or Charles the Great, sought to renew the Roman Empire, resulting in the rise of the Holy Roman Empire, of which he was crowned Emperor in 800 A.D. In the centuries preceding Charlemagne’s rise to power, Europe had experienced a significant decline in literacy. To address this issue, Charlemagne implemented a series of reforms, known as the Carolingian reforms. One of those, the universal education reform, aimed to not only promote literacy and knowledge but also enhance the moral prestige of the empire by making religious texts more legible.

In 782, Charlemagne invited Alcuin of York to his court in Aachen to govern his palace school and scriptorium until 796. In an effort to replace more complex Gallo-Roman and Germanic scripts, Alcuin set about refining Caroline minuscule into an all-purpose script. Its clear, rounded letterforms, uniform heights, and consistent letter spacing made it ideal for copying manuscripts, and by 820 A.D., Carolingian minuscule had established itself as the primary script in the majority of scriptoria. By the end of the 9th century, it had replaced Insular script as the standard handwriting throughout the majority of Europe.

It remained the dominant script for almost four centuries, but underwent significant changes during that time. In France and Germany, for example, Caroline minuscule started diverging from its original form as early as the 9th century. In England, where the Carolingian script was introduced in the 10th century, runic symbols that continued to exist alongside Carolingian letters eventually also influenced them. In Germany, the Gothic script started to develop at the beginning of the 10th century and had mostly supplanted Carolingian minuscule by the 12th century, when the script ceased to be used.

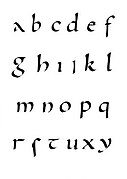

Letterforms used in Carolingian Minuscule

In general, the Carolingian script was written in a four-line system with mostly unconnected minuscule letters and few ligatures. Some letters had ascenders or descenders, meaning parts of the letter extend above or below its main body. Although it was a minuscule script, capital letters were still used for headings.

The letterforms of Caroline minuscule initially developed from Roman half-uncial and the insular scripts common in Irish and English scriptoria. These scripts were characterised by their rounded forms, which were quick to write and easy to decipher — features that can also be found in Carolingian minuscule. During the early stages of its development, spanning Charlemagne’s reign from the late 8th to the early 9th century, additional influences on the characteristics of Carolingian minuscule can be observed, depending on the geographical region. In France and Northern Italy, for example, Merovingian scripts had a greater impact on its letterforms.

Famous Carolingian manuscripts

The explanations above already give a hint as to why Carolingian minuscule has such a great impact on how we perceive history today: Carolingian minuscule was the predominant script used during a large part of the Middle Ages and hence, a vast amount of historically relevant manuscripts were written in it. Here are a few example scripts.

Theodulf Bibles

In the 8th century, numerous versions of the Bible, differing greatly in quality, were being used across Europe. As part of Charlemagne’s agenda to reform the church, the emperor took measures to create a revised version of the Latin Vulgate bible for use throughout the empire. This resulted in the six Theodulf bibles, named after the bishop of Orléans and Fleury who revised the text. Penned in a diminutive version of Carolingian minuscule script, these volumes, meant for thorough scholarly examination and consultation, exhibit corrections and alternative readings noted in the margins.

Moutier-Grandval Bible

Another testimony of Charlemagne’s effort to spread a corrected version of the Latin Vulgate is the Moutier-Grandval Bible. In 796, Alcuin of York was appointed abbot of the monastery of St Martin in Tours. In the years to come, St Martin became an important centre for the mass production of Bibles under the direction of Alcuin and his successors. Three of the fourteen surviving bibles contain exceptional illustrations, marking the high point of the production in St Martin under abbots Adalhard and Vivian. The oldest of these bibles is the Moutier-Grandval Bible, a 9th-century manuscript with pages over half a metre tall and some of the earliest examples of medieval full-page narrative art. It was presumably made around 840 (so after Charlemagne’s death in 814) for the monastery of Moutier-Grandval in the diocese of Basel, hence the name.

Capitulare de villis

Lastly, not only religious texts were written in Caroline minuscule, but also capitularies, penitentiary books, chronicles, mathematical treatises, Canon Law, and so forth. One of the most famous sample secular texts from the Carolingian era is the Capitulare de villis, a document guiding the administration and management of the court estates. This capitulary, dating back to the late 8th or early 9th century, is a renowned source for the history of economics, particularly agriculture and horticulture. It is preserved in a single manuscript housed at the Herzog August Library in Wolfenbüttel, known as Codex Guelferbytanus 254 Helmstediensis. The majority of the writing in the document is in Caroline minuscule, with headings and initials in Uncial.

How to read Carolingian minuscule with AI

Although intended to be more legible, Carolingian minuscule can be time-consuming to read and transcribe manually. Fortunately, thanks to AI, tools such as Transkribus can help historians with the tedious work of manuscript studies.

Unlike regular OCR systems, Transkribus uses cutting-edge Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR) technology to recognise not only printed text but also handwriting in all sorts of historical scripts, including medieval scripts like Caroline minuscule. Users need to scan the pages of the document they wish to transcribe and upload the images to the Transkribus platform. After that, they can select the appropriate AI model for the particular handwriting the document is written in and Transkribus will turn their research material into editable and searchable digital text.

The Transkribus platform contains a whole range of so-called public models trained by the Transkribus team and the Transkribus community. One of these is the Carolingian Minuscule Model CMM 9th-11th c. It was trained on 46 different manuscripts covering the period from approximately 800 to around 1100 and comprising all kinds of genres, including liturgical, clerical, and administrative texts, historiography, and even scientific treaties.

Interested in using Transkribus?

Want to try it for yourself? On this page, you can always try out the model for Carolingian minuscule without having to register with Transkribus. Just upload a test page by dragging it into the designated field and within seconds you can get a taste of the power of Transkribus.

Alternatively, if you are already convinced of what our platform can do, sign up at app.transkribus.org to get the full experience. For an explanation of the first steps in Transkribus and detailed descriptions of its functionalities, visit our Help Centre or check out our YouTube tutorials.

.png?width=1280&height=720&name=Training%20a%20custom%20model%20v2%20(1).png)